Step-by-Step Guide to the ICSI Procedure

Table of Contents

- What is ICSI treatment?

- What is ICSI (Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection)?

- ICSI Procedure Step by Step

- Difference between ICSI procedure and IVF procedure

- Who is the Best Candidate for the ICSI Procedure?

- Associated Risks with ICSI Procedure

- Outlook of ICSI procedure

- Factors Impacting the ICSI Procedure

- Signs of Successful ICSI Procedure

- How Do I Prepare for ICSI Treatment?

- Conclusion

- FAQs:

In recent years, in vitro fertilization (IVF) has revotionalised the field of assisted reproduction treatments, offering a sense of hope to couples facing difficulties with fertility. A key element of IVF treatment, intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), addresses male infertility difficulties and raises pregnancy rates. This article is a crisp manual that will walk you through each phase of the ICSI treatment, give you information on potential risks or complications, cover the outlook for success, and highlight indicators of a successful ICSI procedure.

What is ICSI treatment?

ICSI stands for Intracytoplasmic sperm injection. ICSI treatment is a specialised form and an additional step to an IVF treatment. This treatment is usually used for the treatment of male-factor infertility.

Indications of ICSI treatment:

ICSI procedure is recommended for couples or individuals who have the following reproductive health issues –

- Low sperm count

- Poor sperm morphology

- Poor sperm motility

- Failed IVF procedure

- In case, you require surgical aspiration of the sperm

- In case, you are using frozen sperm

- Embryo testing for a genetic condition

What is ICSI (Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection)?

A single sperm is directly inserted into an egg during ICSI, a specialised method used during IVF to promote fertilisation. When the male partner is affected by fertility issues or experiences problems like a low sperm count, slow sperm movement, or aberrant sperm morphology, the ICSI procedure is often recommended in such cases.

ICSI Procedure Step by Step

Before starting with other aspects of the ICSI procedure, let us first understand the ICSI procedure step by step.

Step 1 – Ovulation Induction

Controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH) is used to induce ovulation and cause the female partner to lay numerous eggs.

Step 2 – Egg Retrieval

When the eggs are ready, a minimally invasive process is used to remove them from the ovaries.

Step 3 – Sperm Collection

Either the male partner’s or a sperm donor’s semen sample is taken.

Step 4 – Sperm Selection

Based on a number of variables, such as morphology and motility, the embryologist selects the healthiest sperm for injection.

Step 5 – Embryo Fertilisation

A single sperm is injected into an egg with the use of a microneedle to facilitate fertilisation.

Step 6 – Embryo Development

The fertilised egg (also known as an embryo) is incubated for a few days until it reaches the correct developmental stage.

Step 7 – Embryo Transfer

One or more embryos are chosen and placed in the woman’s uterus.

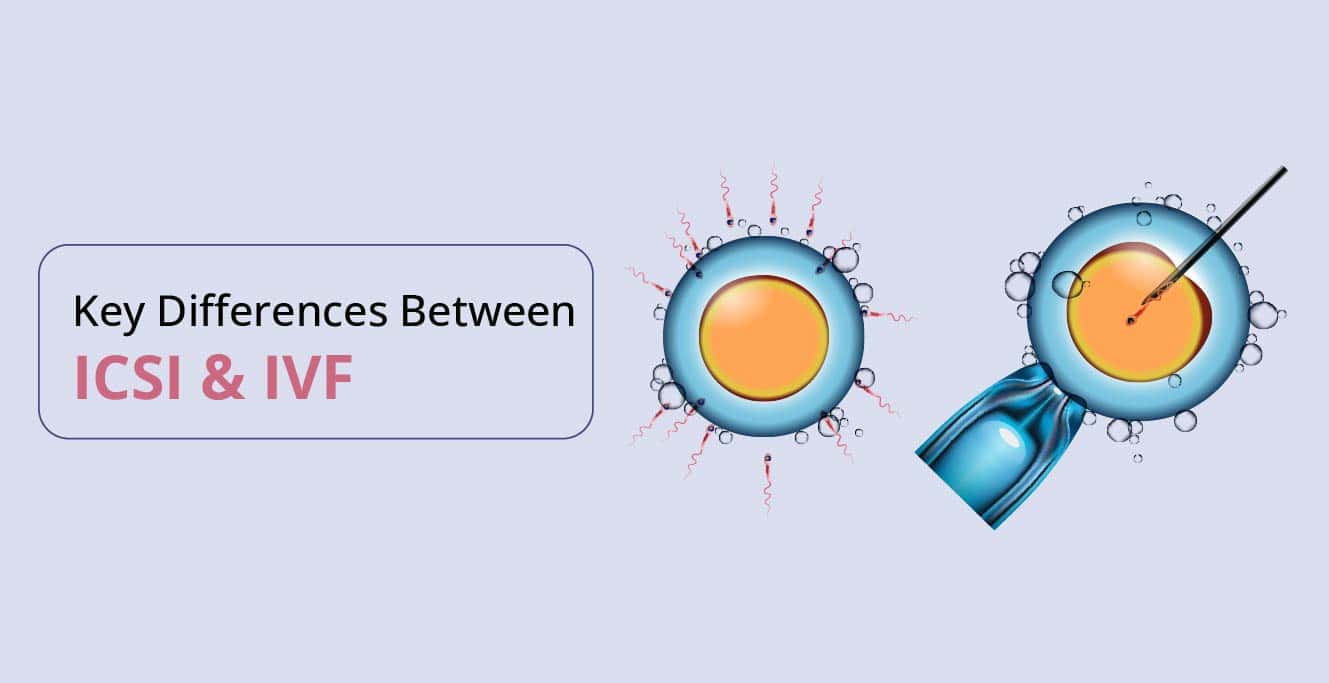

Difference between ICSI procedure and IVF procedure

Both intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) and in vitro fertilisation (IVF), which are assisted reproductive treatments, have different applications and execution techniques. The following is a significant difference between the ICSI procedure and the IVF procedure:

- ICSI: ICSI is a method of fertilisation where a single sperm is directly inserted into a single egg to aid in fertilisation. When a man experiences male infertility problems, such as a low sperm count or poor sperm motility, this procedure is typically performed.

- IVF: In IVF, sperm and eggs are combined in a test tube to promote natural fertilisation. It excludes direct sperm injection into the egg.

Who is the Best Candidate for the ICSI Procedure?

For couples struggling with male infertility, the ICSI procedure is typically known as the best option. The following conditions may also lead to the doctor’s recommendation for ICSI procedure:

- Anejaculation, the inability to ejaculate

- Low sperm count

- Any type of male reproductive system obstruction

- Poor sperm quality

- Retrograde ejaculation: semen fluid flowing back into the bladder

Additionally, the doctor might advise an ICSI procedure if

- Traditional IVF attempts made repeatedly don’t result in embryo development.

- When using frozen eggs or sperm, the female must be over 35.

Associated Risks with ICSI Procedure

Although the success rates of IVF have considerably increased because of the ICSI procedure, there are still some hazards to be aware of, such as:

- Genetic Abnormalities: Although still a very low risk, there is a modest increase in the incidence of genetic abnormalities in children born with the ICSI procedure.

- Multiple Pregnancies: Using several embryos can increase the possibility of twin pregnancies or higher-order multiple births, which may pose health risks to both the mother and the unborn children.

- Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome (OHSS): OHSS is a potentially serious condition that can result from excessive ovarian stimulation.

Outlook of ICSI procedure

ICSI has given many couples hope, yet results vary from case to case. The quality of the embryos, the woman’s age, and the underlying cause of infertility all affect the likelihood of success. Younger women typically have better success rates.

Factors Impacting the ICSI Procedure

Here are a few contributing factors that can influence the success rate of the ICSI procedure:

- Age: Women under 35 often have better success rates than older women.

- Embryo Quality: Successful pregnancies are more likely to arise from high-quality embryo implanting.

- Underlying Causes: Whether a female or male component is the reason for infertility, it can affect the outcome of the ICSI procedure.

Signs of Successful ICSI Procedure

Some of the positive signs after the ICSI procedure are:

- Implantation Bleeding: A few days after embryo transfer, some women suffer minor bleeding or spotting, which may indicate successful implantation.

- Increasing hCG Levels: Pregnancy can be determined by blood tests that track hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin) levels.

- Ultrasound Confirmation: A few weeks following embryo transfer, ultrasound examinations can usually identify a developing foetus and its heartbeat.

How Do I Prepare for ICSI Treatment?

ICSI is a complex procedure that requires extra attentiveness and care from both the fertility expert as well as the expecting couple. While some factors may not be under your control, there are certain steps you can take to help boost your chances of conception through ICSI treatment.

Given below is a list of measures you can take to help you prepare for ICSI treatment.

Eat a healthy, nutrient-dense diet

When planning pregnancy, it is important to eat a healthy and well-balanced diet before conception till delivery. Whether you are conceiving naturally or through fertility treatment, eating healthy meals is important. In the case of ICSI treatment, it is suggested that you should eat more fruits and vegetables (especially green vegetables). Additionally, you should include the following food products or items in your diet:

- Lean protein like fish

- Whole grains like quinoa and whole-grain pasta

- Legumes like beans, chickpeas, and lentils

- Low-fat dairy

- Healthy fats including avocado, olive oil, nuts and seeds

On top of these, you should avoid eating red meat and also reduce your salt intake.

Start your prenatal vitamins

Unlike popular opinion, the significance of prenatal vitamins starts early on. You should start taking your supplements before you plan the pregnancy or during the early stages of conception. Your fertility doctor will prescribe the right prenatal supplement.

Maintain a healthy weight

Your body weight plays an important role in not just your chances of conception but also in maintaining a healthy pregnancy. You should eat a balanced diet and exercise regularly to avoid gaining extra weight. However, you should ask your fertility doctor before starting any exercise routine. It is suggested that you should have a consistent, safe and light fitness regime. Practice yoga, walking, spinning, and light jogging.

Avoid unhealthy behaviour

There are several substances that can impact your chances of pregnancy through an ICSI treatment. It is, thus, mandatory to ensure that you are practising healthy behaviour and keeping clear of unhealthy patterns and substances. It is strictly advised that you should avoid the consumption of alcohol, smoking, and tobacco. In addition, you should also aim to reduce your caffeine intake.

Manage stress levels

High-stress levels are known to have a negative impact on your fertility treatment. ICSI treatment can also be affected if you are consistently under stress. It is suggested that you manage your stress levels by engaging in healthy activities such as yoga, meditation, and journaling. These measures can help you to increase your chances of conception, especially yoga as it can help boost your blood circulation to reproductive organs, decrease tension around the hips and pelvis, improve endocrine function, and provide greater levels of peace and calm.

Conclusion

Although both ICSI and IVF are effective assisted reproductive technologies, they are applied in distinct circumstances. IVF is a more flexible alternative for a variety of infertility causes, whereas ICSI is designed for situations of male infertility or when prior IVF attempts have failed. The result of remarkable developments in assisted reproductive technology is referred to as intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), which gives infertile couples hope to achieve pregnancy and start a desired family. The ICSI procedure, potential risks, the likelihood of success, and indicative signs of a successful ICSI procedure have all been covered in detail in this step-by-step manual. ICSI has its difficulties, yet it has helped many couples realise their dreams of parenthood. Keep in mind that every journey is distinct, and speaking with a reproductive specialist is essential to comprehending your particular situation and available options. If you are diagnosed with male infertility and struggling to start a family, consult our fertility specialist today by calling us or booking an appointment with us by filling out a given form with all the necessary details.

FAQs:

- What are the benefits of the ICSI procedure?

Here are a few benefits of the ICSI procedure:

- By manually placing healthy sperm into an egg, it effectively ends male infertility and increases the likelihood of conception. It also does this by getting rid of any pollutants that might have contributed to male infertility.

- Before insertion, examine the sperm’s motility, shape, and structure, as well as its count.

- Beneficial for those who have undergone an irreversible vasectomy or are paralysed

- Is the ICSI procedure more complex than IVF?

ICSI may require more precision compared to IVF because it entails precisely injecting sperm into each egg, ICSI is a highly specialised and complex operation. On the other hand, IVF relies on the natural fertilization process taking place in a lab setting, IVF is a less invasive and complicated technique.

- Why is ICSI recommended for patients?

Below are some of the common reasons why ICSI treatment is recommended by experts to patients in need:-

- Low Sperm count

- The quality of sperm is bad

- Affected sperm motility

- Sperm structure abnormality

- Does stress have a negative impact on ICSI results?

High levels of stress have been shown to have a detrimental effect on fertility treatments. If you are regularly stressed out, your ICSI therapy may also be compromised. You are advised to control your stress levels by partaking in stress-relieving exercises like yoga, meditation, and journaling.

- What is the full form of ICSI?

ICSI is the acronym for intracytoplasmic sperm injection. It is an advanced IVF treatment that involves injecting a single sperm directly into the egg using a fine glass needle.

Our Fertility Specialists

Related Blogs

To know more

Birla Fertility & IVF aims at transforming the future of fertility globally, through outstanding clinical outcomes, research, innovation and compassionate care.

Had an IVF Failure?

Talk to our fertility experts

Our Centers

Our Centers